|

1 like

42 comments

share |

4 min reading time

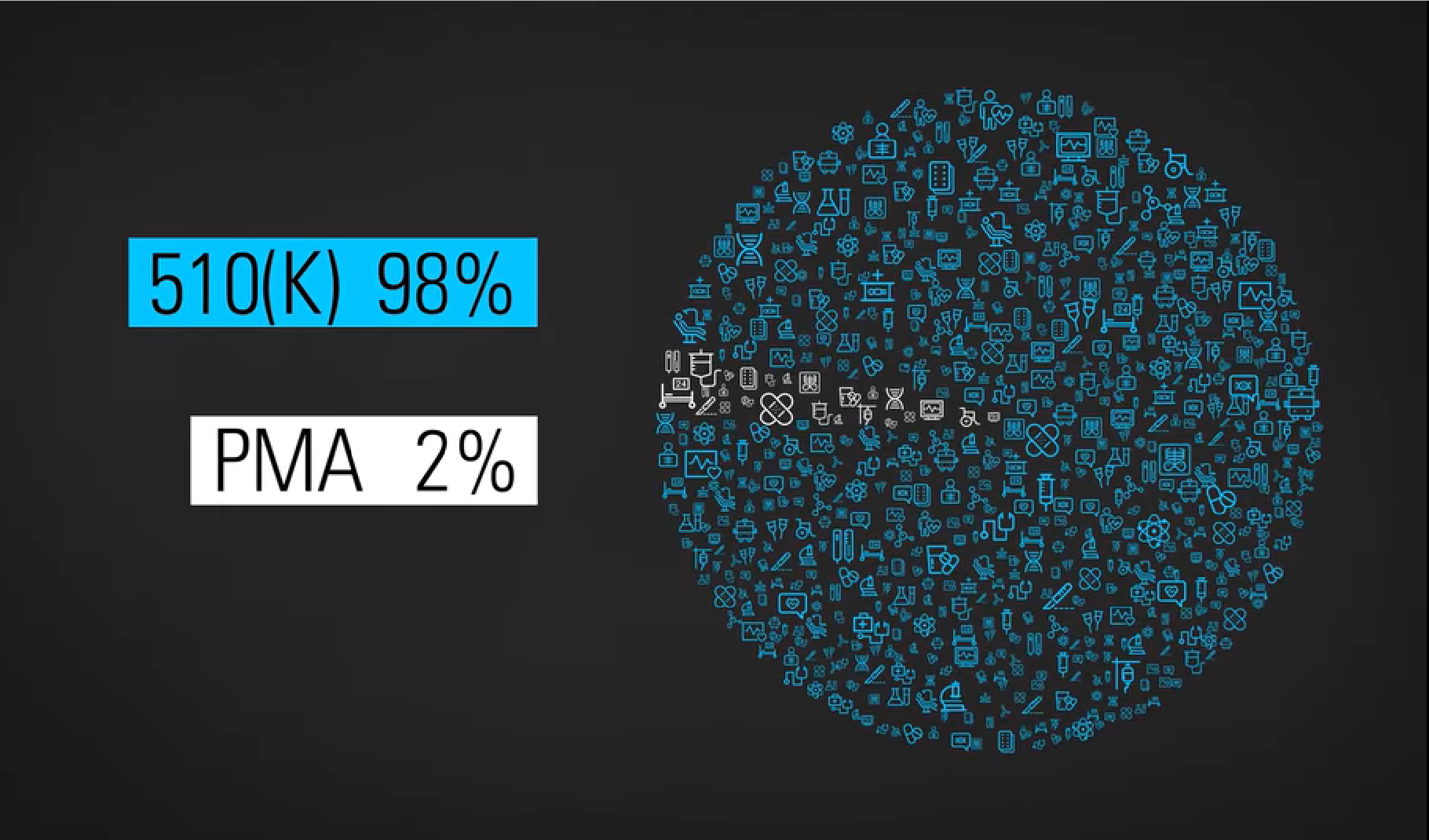

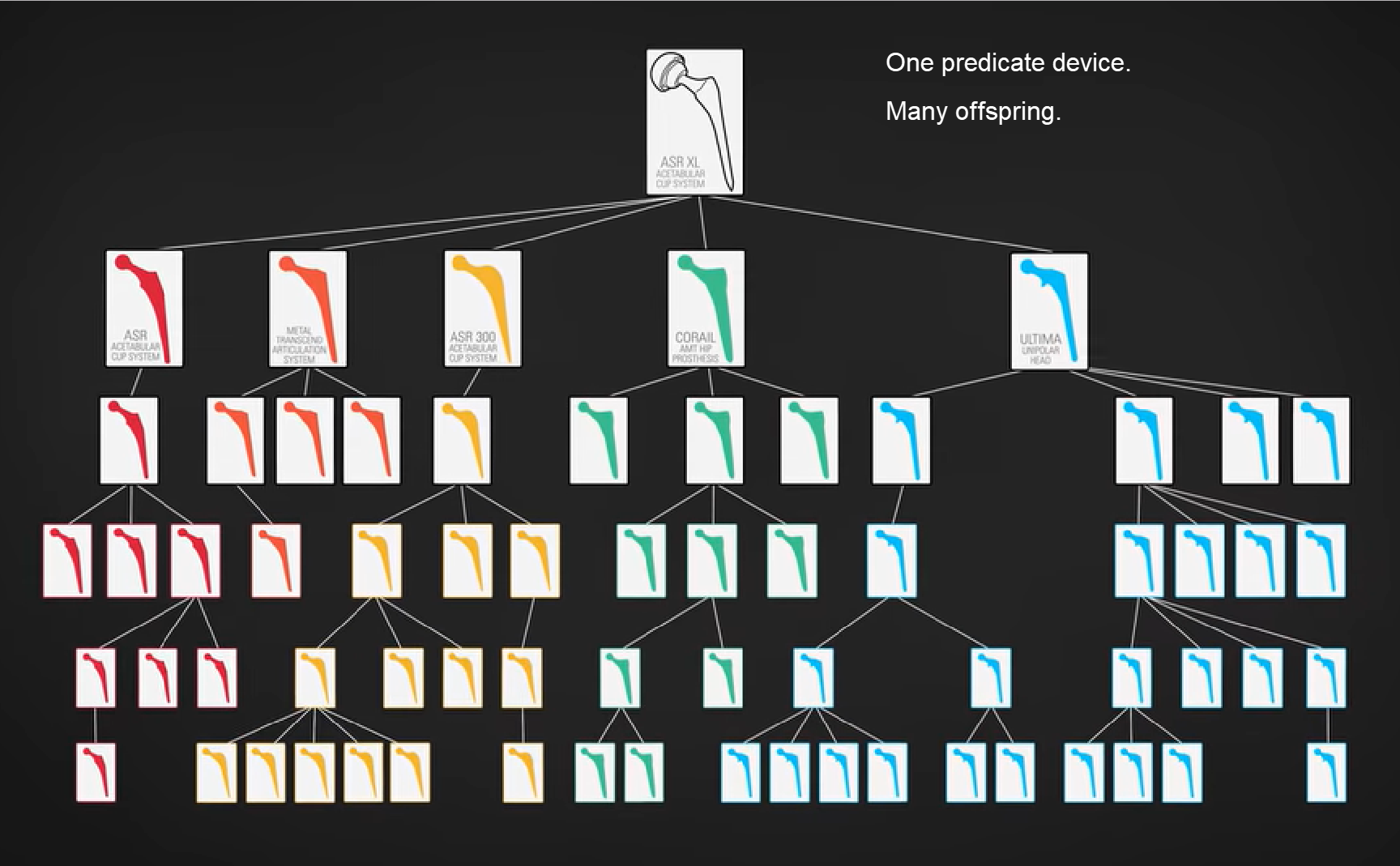

First, I have to say how liberating it is to be writing you on my own site versus LinkedIn. I literally feel a wave of relief washing over me. First, I don’t have to count characters. Second, I’ve already used italics(!), something LinkedIn doesn’t support. Oh! What will follow: Bolding! Color! Images! Video! Hyperlinks! I should have done this a long time ago – and if you haven’t registered for this specific site yet, please take a moment and do so now, so I can continue to communicate Medical Devices Group messages to you. (Your LinkedIn group membership does not automatically extend to this WordPress-based website.) Kessler’s RegretI was going to discuss the much-discussed Netflix documentary, “The Bleeding Edge” today. (Here is a direct link to the documentary for Netflix subscribers.) But the group could not wait until Tuesday! Three submitted discussions this week about it. I finally published Amy DeWinter’s commentary and it racked up two dozen comments in no time. There is so much to unpack in “The Bleeding Edge.” I’ll likely return to it in the future. But they covered something so interesting about our 510(k) path to FDA clearance in the first 20 minutes, I couldn’t get past it. Direct excerpts from “The Bleeding Edge”These are intended for context for our discussion. Dr. Michael Carome, Director, Public Citizen Health Research Group [Carome]: Most people probably believe, when they get a medical device implanted, be it a pacemaker or a joint, that those medical devices have undergone appropriate testing to demonstrate that they are safe and effective before they came on the market and doctors started using them. But for most moderate and high-risk devices, that is not the case. William K. Hubbard, Former FDA Associate Commissioner: Originally, Congress intended that almost all new devices go through pre-market approval (PMA). A PMA is similar to a new drug application, in that a manufacturer must test it first in humans, compile all this data, and then present that to FDA scientists, who will approve the device if in fact it is safe and effective. Industry argues, “We’re innovating, we’re changing products every year and that costs a lot of money, to test each of those iterations in humans.” So Congress established the 510(K) process. Carome: For the 510(k) pathway, all the manufacturer needs to demonstrate is that their device is substantially equivalent, is the regulatory term, to another device that’s already on the market. Dr. David Kessler, FDA Commissioner, 1990-1997: Dr. Adriane Fugh-Berman, Professor of Pharmacology & Physiology, Georgetown University: This really can cause problems when one medical device is approved on the basis of being substantially equivalent to a previous medical device that was approved because it was substantially equivalent to an earlier medical device than that. Dr. Deborah Cohen, Associate Editor, British Medical Journal: You end up with what we call a daisy chain. And then, quite often what you found is that some of these predicate devices, as they call them… have been recalled from the market because they’ve been failing.

Jeanne Lenzer, Author, The Danger Within Us: I called the FDA and asked them, “How can you clear something based on a predicate device that’s already been shown to be dangerous? And they said, “We don’t judge what the prior device is.” Dr. Rita Redberg, Editor, JAMA Internal Medicine: So even if the device was recalled because it was dangerous, you can still use it as a predicate and get your device cleared ’cause it’s substantially equivalent. So there’s a lot of problems with that 510(k) system. Your TurnSo there we are, folks. The current state of the 510(k) pathway. Does it make you feel safe… especially that part about basing your device on a failed predicate?! Yikes! “The Bleeding Edge” documents a number of devices gone terribly, terribly wrong. What say you? Should FDA stop recognizing the 510(k) a pathway for clearance? Should they markedly reform it? Leave it alone? I can’t wait to read your robust comments – which(!) – you can receive as alerts(!!) – when subsequent members leave their comments. Immediate access to all four FDA’s Case for Quality webinars.Click here for the FDA content, courtesy of Jon Speer and Greenlight Guru. Guys, it doesn’t get much better than this. Cisco Vicenty presently works at FDA as the FDA Case for Quality program manager. Subscribers asked direct questions during the live event. A worthwhile recap for everyone in QA, RA, Clinical Affairs, R&D, and any kind of medical device engineering. Want to meet in person?As leader of our Medical Devices Group, I host a few events annually to meet and help members in person. Here are my upcoming events (updated June 2019):

Fast RoundAnother new feature, I’ll close most weeks with short stories, links of interest, sponsored ads, and more. Is there something our community should know about? Contact me and tell me all about it. I’ll reply as quickly as I can.

Thank you for being part of our Medical Devices Group community.Make it a great week. Joe Hage Marked as spam

|

Meet your next client here. Join our medical devices group community.

Private answer

If I recall Dr. Kessler's reign as the head of the FDA, he was somewhat disruptive. I do recall then when device regulation was implemented in the Spring of 1976, innovation was interrupted, for a time. The 510k path was implemented to regulate/register products that had very low risk but were essential to healthcare. It was not a bad decision have the 510k pathway. Furthermore, even though there may be some flaws in the 510k approval process, it does provide the FDA to review, approve, reject or suggest resigning the product to a different classification for potential approval. In essence, the FDA has the final word.

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Luis Chavarria

This has global implications. For example many countries fast track approvals in their systems if the device already has a 510k from the USFDA.

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Anil Bhalani

Dr. Kessler called it regrettable because he was of the opinion that devices should not be approved using a 510(k) pathway. If he had his way every device would have some degree of PMA approval. I beleive you think that Dr. Kessler said the process was regrettable......it should be easier; which is not the case. Dr. Kessler changed a lot. Tougher but good for patients. For instance (1) Design Controls (2) I believe he started the movement to regulate cigarettes as drug delivery devices.

I think the FDA regulatory process, although need many wrinkles ironed out, is still the best. EU is purely a paper exercise that they are trying to change. It is a financial bonanza for consulting companies and notified bodies, where you can still get a CE mark for something that does not work. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Anil Bhalani

The 510(k) process is a good process. My experience from the corporate world and from my consulting is that people lack experience and understanding and the focus is to get an approval. Never had a problem knowing if the device would get a 510(k) or will be a struggle. The process is quite transparent now. The tough part is finding the right predicate or not having one for new devices with new applications that are low risk. The De Novo process was meant to help here but does not work well every time.

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Ultimately, a balance must be struck between the regulatory hoops necessary to ensure public safety and efficacy, and the streamlined approval system necessary to promote innovation, accessibility, and competition. 510(k) clearance was likely introduced with that in mind.

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Julie Omohundro

The 510(k) regulation was passed in 1977, the same year Kessler graduated from law school. He was in no position to know what the regulation was "supposed to" be and is simply repeating what he was told years later, by people who "remembered" the purpose of the legislation however best suited their current agendas.

Moreover, as with any legislation, even at the time it was crafted and passed, different players undoubtedly had their own ideas of what it was "supposed to" be. The notion that a legislature made up of hundreds of legislators, all with their own agendas, being advised by individuals who have their own agendas as well, has anything remotely approximating a will has always struck me as nonsensical. Dictators and monarchs have a will. With a legislature,a bunch of agendas collide, and legislation comes out the other side. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Julie Omohundro

My own impression of the original Amendment is that it was astonishingly myopic. (And it takes a lot of myopia to astonish me.) The idea that every type of device was supposed to be catalogued in individual regulations reminds me of the (probably apocryphal) story of the head of the US Patent Office who resigned at the turn of the century, because he thought surely everything that could be invented, already had.

This only makes (some) sense if the 510(k) process was supposed to be pretty much "done" once all of the existing device types had been classified, and that very little innovation was anticipated going forward, with the occasional "new" device being approved via the PMA path. The only way FDA could avoid turning 21 CFR into an encyclopedia was to cram as many different devices into each regulation as possible. Thus the product codes. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Julie Omohundro

Anil, the amount and type of data needed to support the safety and effectiveness of a device is determined by its technology and its intended use. You can run it through any regulatory pathway, or no pathway at all, and the data requirements do not change. These requirements must be identified by the developers in a risk analysis. They cannot be identified by the FDA in a regulation or guidance, because one size does not fit all and IT"S NOT THEIR DEVICE.

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Mark C Adams, MBA

In my opinion it’s the FDA at fault.

Their loose interpretation of predicate devices is the root cause of the problem. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Julie Omohundro

Mark, I don't disagree with the loose interpretation, but I think the myopic legislation was the root cause of the loose interpretation, along with Congress' perennial failure to resource FDA at the level that would enable it to do otherwise. (Congress has always loved to pass laws that require federal agencies to do many things, but fund those agencies to do the things well, not so much love there.)

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Binseng Wang

Please read my commentary on The Bleeding Edge posted at http://www.24x7mag.com/2018/08/technology-innovation-causing-bleeding/?ref=fr-title . Feedback is most welcome. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Dave Sheppard, CMAA

There is a fine line between too much regulation and too little. If we’re talking improvements in process in the U.S., what I would love to see is a CMS reimbursement code along with every FDA clearance. This would help improve the ecosystem of innovation in the U.S. as investors would be more likely to invest in early stage companies if there was a clearer line of sight to reimbursement. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Joe Hage

Wow, @Dave Sheppard. You really are a dreamer! One problem at a time, please! Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Robyn Barnes

I was concerned about this predicate device situation when I had my knee replaced. Before the replacement, I asked my doctor for all the details about the part he was going to use. I have the good fortune to work with someone who had designed knee joints and I took this information to him to ask if the part was really FDA approved and if it was a “good” part. He said the doctor had chosen well and not to worry. So far, no problems. Not everyone has a friend like mine, though, so I wonder how the average patient would know about the quality of the part the doctor will use. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

In today’s digital workflow, disallowing a prior “allowable predicate” should be a matter of disallowing and then citing that to companies who used the predicate to show that the disallowence did not affect their submission because “………” and then “in addition we have ………” or “we have changed our product so it is resubmitted with a new acceptable ‘feature’, so that the newer device has a reasonably manageable pathway to maintaining integrity in the system. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

I work in med device distribution, I’m shocked and disappointed in the FDA. I think politics must have been in play here. I would like to know more about how 510k came about and why an addendum hasn’t been put in place to show equivalencies to a failure, hold or recall. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

I agree the 510k pathway most likely needs to be revised to include ongoing review as needed. In cases where a predicate recall occurs, all subsequent approved devices under that equivalent should go under a comparative analysis review to see if further testing needs to be performed. We can’t get bogged down in the paperwork and bureaucracy and miss the whole point of doing this, the safety and care of patients. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

John E. Lincoln

I have found that most reviews of 510(k) submissions are painfully thorough, more so than often warranted. The areas I feel that has the greatest potential for problems in not identifying past adverse events / recalls as mentioned above is the 1) Classification regulation (8XX.series), 2) Panel, and 3) Product code decisions required for any 510(k) submission. Anyone who has done 510(k)s knows that a predicate can be located udenr several different variations of those 3 categories. Since such inconsistency exists it is difficult to identify problem with a device family in any database, in that a problem will be listed under the category of the failed device reported, and not linked to the identical product family under one of the other three categories. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

John E. Lincoln

I also remember that Dr Kessler had to deal with a major problem with 510(k)s in the 1990s. That there were few if any 90 day reviews, but that most 510(k)s were backlogged at the Agency for up to 200 days and beyond. I’m not sure that going the PMA route for all devices, which can take several years is the best use of limited resources (at the FDA or with industry). Look at problems with drugs, which are subjected to much more lengthy review and still have problems when rolled out into a larger population than any clinical trial could reasonably address. I would still argue that better database data tied to device family offers the best near-term solution. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

In my mind the overarching issue is not solely limited to regulatory pathway. FDA clearance, no matter the pathway, is nothing more than a “ticket to the dance” and does not drive reimbursement or codes. Likewise, codes do not guarantee coverage or reimbursement. Physician focused product development in the “if we build it they will come” model is largely obsolete as CMS, commercial payers and IDN’s are willing to declare FDA cleared devices (even with codes) as experimental and investigational or not medically necessary. While not universally required (yet), compelling evidence of value for money compared to SOC is just as important as physician acceptance. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

The only thing that's truly regrettable is David Kessler being appointed to FDA Commissioner. Under his guidance, he practically dismantled the logic of device review and approval process... insisting that bio-medical engineers were the wrong professionals for med device review... favoring, instead, MD's who may have had very little if any insight to design reviews, FMEA, quality systems, etc., etc. Had the 510(k) process never happened, med device technology as we know it today would have lagged years behind our global competitors. Thankfully, wiser heads prevailed... as did the implementation of a Substantial Equivalence paradigm that included and required demonstrable patient risk-to-benefit. As for the good Dr. Kessler, he departed FDA and returned to academia... holding a position at Yale for several years and then, after some difficult times there, wound up at UCSF... where he was ultimately forced to resign and dismissed in 2007. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

1. I cannot help but note that the documentary only emphasizes negative device experiences. MOST devices do help us live better, healthier and/or longer. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

John E. Lincoln

Another argument for better post-market categorization, reporting and tracking is the phrase “legally marketed” relating to predicates, e.g., “any legally marketed device may be used as a predicate. Legally marketed also means that the predicate cannot be one that is in violation of the Act.” — https://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/howtomarketyourdevice/premarketsubmissions/premarketnotification510k/default.htm Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Louis J. Mazzarese

The only thing that’s truly regrettable, is David Kessler being appointed to FDA Commissioner.

Under his guidance, the device review and approval process was significantly undermined…..he insisted that bio-medical engineers were the wrong professionals for med device review…….favoring, instead, a preponderance of MD’s , many of whom coming from pharma, with little if any insight to design reviews, FMEA, quality systems, etc., etc. Had the 510(k) process never happened, med device technology as we know it today would have lagged years behind our global competitors. Thankfully, wiser heads prevailed…as did the implementation of a 510(k) Substantial Equivalence paradigm that included and required demonstrable patient risk-to-benefit. As for the good Dr. Kessler, he departed FDA and returned to academia….holding a position at Yale for several years..... and then, after some difficult times there, wound up at UCSF…where he was ultimately forced to resign and dismissed in 2007. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Julie Omohundro

Louis, I think your comments could easily be expanded into multiple discussion topics, but could you briefly expand a bit on "Had the 510(k) process never happened, med device technology as we know it today would have lagged years behind our global competitors"?

I would be particularly interested in more detail on exactly how the 510(k) supported global competitiveness, by what measure (sales?), which global competitors you think would have been years ahead of the US otherwise, and why. (All in 1,000 characters or less, lol.) I expect many people here who were not around during this period would find this interesting as well. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Working for a company that is selling a device in the US through 510K clearance that we make in Australia, I have to say that the whole process for 510k worries me. I trust in our product, but it does concern me how easy our reg person manages to get approval for new product lines when we are struggling to get it through our own TGA and are grilled through our notified body in the EU as well. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Louis J. Mazzarese

Gladly.......

During and after Kessler's tenure at FDA, there were those, both in and outside of the Agency, who strongly believed that many Class II medical devices should only be approved based on prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled clinical trials testing. If they had succeeded, while the EU, for example, approved their class II devices based on compliance with standards and w/o requiring prospective clinical testing, the US devices would have been at a serious competitive disadvantage in terms of the cost of product development and the time to market. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Julie Omohundro

But I don't see what that has to do with the 510(k). I know of nothing in the 510(k) regulation that excludes the need for a prospective, double blind, randomized, controlled clinical trial. Conversely, I know of nothing in the PMA (or De Novo) regulation that requires one.

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Lakshman Srinivasan

In my experience, 510k starts at substantial equivalence. It doesn’t stop there as the remarks seem to suggest. You still have to submit your own intended use, risk management, design controls, etc. 510k clearance has never been a “substantial equivalence” farce as has been portrayed here. Besides, there are audits which revisit every aspect of your design, risk management, manufacturing, post-market, etc. There can also be a legitimate reason why a successor to a substantially equivalent recalled device can be allowed on the market. The flaw that caused the recall could have been fixed in the new device. One of the items submitted is review of past complaints, recalls, etc, of predicate devices, even competitor devices, with a clear explanation of how the new device addresses each. Now, if the FDA and other agencies don’t check whether the submission included the recalls they are aware of, that is an easily correctable gap in the regulatory agencies’ process. In the end, there is typically residual risk associated with every device. The important thing to look at is whether the risk controls, and risk-benefit analysis have satisfied the regulators, and whether the residual risks have been properly disclosed to users in customer documents. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Binseng Wang

As I said in my article on 24×7 (see link in prior comment), one of the main problems is political interference on FDA. I think one solution would be to make FDA more independent, like the Federal Reserve, with officials appointed for an extended period of time (14 years in the case of the Fed) and whose decisions do not have to be ratified by the President or anyone in the Executive Branch. This would require a new law by the Congress. What do you think? Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Netflix’s “Bleeding Edge” is an anti-business production masking as pro-consumer. It reminded me of many a 60 Minutes production. I happened to have close-up knowledge of two of their pieces; the facts were grossly distorted to push a certain agenda that sat well with CBS. There’s good reason why many of my regulatory clients clear JUST ABOUT ANY MARKET IN THE WORLD before they tackle the US–FDA is harder, and often ridiculously so. The documentary focused on devices that bump up close to the PMA line; there’s no reason to believe they would have performed better had they gone that route instead of 510k (one of many inconvenient truths overlooked by the producers). Take cobalt leakage in implant prosthetics (yes, a health disaster–if the facts as presented are accurate). Would you have all devices go through 5 years of testing (and in humans, to boot) to see if something pops up that “soon”? Ditto for the sterility implant. And the vaginal mesh (and why wasn’t it resorbable? that’s what hernia mesh fixation devices are now). Some reforms I’d like to see at FDA… 1. Stop recognizing the “latest” electrical safety and EMC test standards from IEC. The vast majority of devices cleared today would operate just as safely and effectively under versions in effect decades ago. Meanwhile the cost of those two tests alone have skied from under $10K to $45K, and this for products that often sell for $500 or less. It’s no surprise so many devices are marketed illegally; their promoters can’t afford the barrier to entry. Not surprisingly, Big MedDev supports the costlier standards. 2. Pull back on performance testing, especially for devices that won’t “harm” if they don’t “work” (besides, most performance testing is of marginal value). This approach would make De Novo a more sensible pathway, and also lead to a user fee more in line with 510k than PMA. Let the market sort through winners and losers. Leave FDA to ensuring safety. All regulatory agencies get captured by those they regulate. Turning FDA into the Federal Reserve of food, drugs, cosmetics, and devices wouldn’t affect that–look at how Wall Street controls the Fed. We have BANKERS in charge of the BANKING system. Real smart, eh?! I’m glad someone pointed out that predicates must be legally marketed. That slanted rant in “Bleeding Edge” was standard journalistic malpractice. Some would even call it “fake news.” Many of the past decade’s changes on the device side of FDA have been for the better. Turning the difficult 510k/De Novo pathway into an ugly twin of the impossible PMA route would be an enormous step backward for American citizens (good for my business, but a disaster for users). We can certainly make improvements in adverse events reporting. And other areas, too. Torching the 510k program because a handful of devices prove disastrous is hardly the right prescription. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Joe Hage

So many rich commentaries here. Thank you to everyone who shared their passion and time with our community. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

John Gillespy

510k is for "moderate" risk devices, which sometimes require animal studies or human trials to satisfy safety and effectiveness concerns. De Novo also is for moderate risk devices, but they often require animal or human performance tests (but certainly not prospective etc) due to novel intended uses and/or technologies. PMA is for "high" risk devices, which rightly call for comprehensive animal studies and/or human trials.

Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

This format works great, Joe. BTW, the answer to, should a predicate failure affect 510(k) status? One answer would be, “It depends on what failed and why.” A broader point would be to ask if invalidating the 510(k)’s must imply that the PMA was done incorrectly, or whether the failure was not the result something done incorrectly on the auditor’s part. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

John Abbott

The comment by Dr. Michael Carome above, while technically correct is really not true in practice. Yes, the 510(k) process does evaluate new devices against previous approved ones however, the FDA’s criteria for accepting substantial equivalence claims requires that the submitter provide a considerable amount of data (proof) on the device’s safety and effectiveness to demonstrate that substantial equivalence. That is, the FDA requires you to show substantial equivalence in terms of safety and effectiveness (not just shape or color or intended use). You cannot just send a one page letter stating that your device is the same as some other one already on the market and you are good to go. And that justification can run hundreds of pages and often includes clinical and bench test results. The last 510(k) I did was about 2 inches of paper when printed out. So, does the 510(k) result in devices that are “safe and effective”? Absolutely! Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Joe Coughlin

This 501(k) is deeply flawed. It was built with good intentions but as decreased quality of later products emerged they got a free ride on the coattails of previously quality products because of the structured language on the purpose of the 501(k) to expedite leading-edge technology. This has been a costly experiment which has jeopardized many patients and placed increased financial burdens on a vast scale. Marked as spam

|

|

Private answer

Michael Tar

To Dave Sheppard’s point, the FDA and CMS established a “parallel review” pathway in 2010… and to date we have seen only two such approvals — both IVD systems. I agree that CMS should be the first test of whether your device will “fly”, followed by Kaiser. Decide what claims will earn their business, and begin your clinical strategy there. Jim Harmon also makes an excellent point: The days of handing the hospital buyer a 510(k) letter and jogging into the locker room are long over. Today’s hospital approvals take longer and are more expensive than regulatory approvals. Then there’s the ever-slowing rate of physician adoption. As hospital systems consolidate, and doctors become their employees, their levers get shorter while litigation risk is higher than ever. Essure, the morcellator, mesh, and other debacles have poisoned the pool — nobody wants to be the first to jump in, lest there be sharks… See you all at RAPS! Marked as spam

|

We still use LinkedIn to access our site because it’s the only way to “pull in” your LinkedIn photo, name, and hyperlink to your profile page, all vital in building your professional network. When you log in using LinkedIn, you are giving LinkedIn your password, not me. I never see nor store your LinkedIn credentials.